JonathanFulton:Assistant Professor of Political Science atZayed University Nonresident Senior Fellow at The Atlantic Council

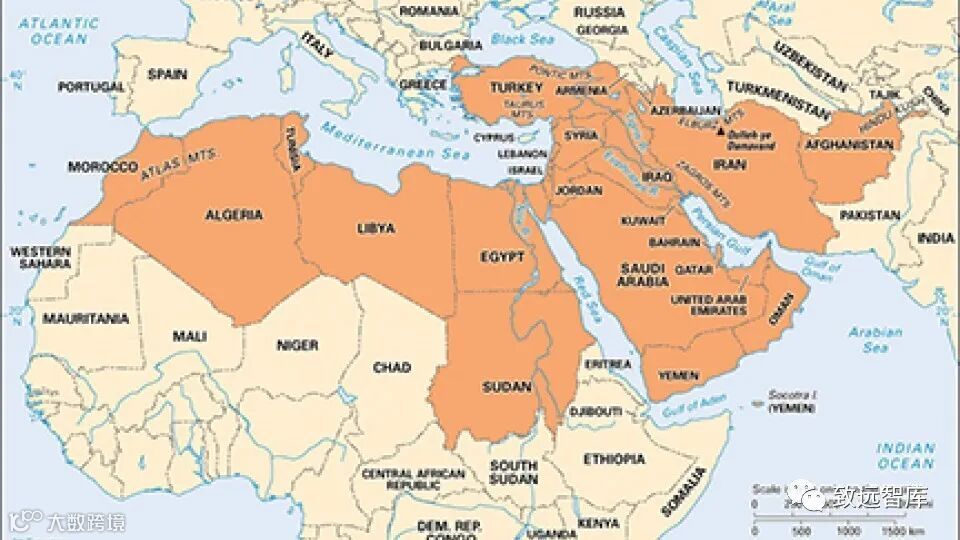

In January 2022, six Middle Eastern foreign ministers and the secretary-general of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) traveled to Wuxi, China, to meet with their Chinese counterpart Wang Yi. Soon after this visit, Chinese Defense Minister Wei Fenghe and Saudi Deputy Defense Minister Prince Khalid bin Salman held an online meeting to discuss issues of mutual interest, with Wei saying the two countries should “strengthen coordination and jointly oppose hegemonic and bullying practices to safeguard … the interests of developing countries together.”

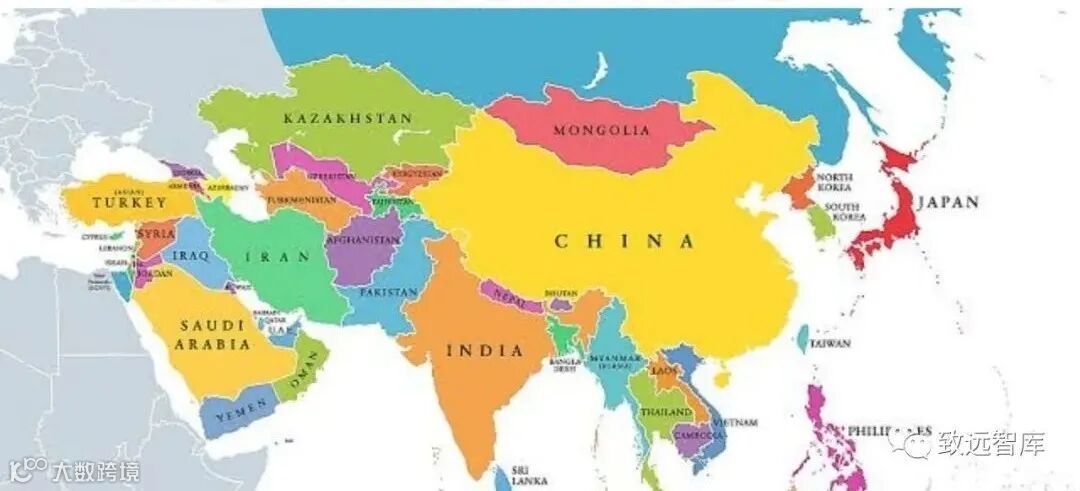

When Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan and Qatari Emir Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani met in Beijing at the opening ceremony of the Beijing Winter Olympics, it further emphasized the critical role China has come to play in Gulf affairs. Less obvious is that this is part of a larger trend as Asian countries, in general, become more and more active in the Gulf, not just at the economic front but also politically and in security affairs. Writing at the dawn of the post-Cold War era, Japanese author Yoichi Funabashi described a phenomenon he called the “Asianization of Asia.”

Funabashi wrote: “As Asian nations phase out the specialrelationships they have had with former colonial powers and integrate with theglobal economy, they are starting to see neighboring countries as trading partners, providers, of investment opportunities and competitors” Now, 30 yearslater, we witness a more expansive Asianization as Gulf governments, businesses, investors, and people integrate with their Asian neighbors.

Beyond Energy

The economic side of the story is already well documented. China, India, Japan, and South Korea are among the top trading partners of all GCC countries. Essential requirements for energy imports mean Asian countries will continue to be important markets for Gulf producers. It is more than energy, however. More than 50 percent of global GDP is projected to come from Asia by 2040, making it an important region for Gulf trade and investment. The global economic center of gravity was positioned in the middle of the North Atlantic in 1980; by 2050, it is expected to be squarely between China and India.

While the China-MENA stories were in the spotlight in early 2022, South Korea’s President Moon Jae-In and Thailand’s Prime Minister Prayut Chanocha also made substantive trips to the Gulf. During Moon’s visit, he stopped first in the UAE, where a deal worth $3.5 billion was signed for Cheongung II mid-range surface-to-air missiles. He then went to Riyadh, where it was announced that Korean electronics giant LG would set up a regional headquarters there. The proposed South Korea-GCC free trade agreement was on the agenda in both countries. Just days later, Chaocha was in Riyadh for the first high-level Saudi-Thai meeting in 30 years.

This is a pattern that has been long in the making. Pre-pandemic official travel from the Gulf was indicative. Saudi Crown Prince Mohamed bin Salman made high-profile visits to Pakistan, India, and China in February 2019, signing major investment deals in each. Qatar’s Emir Tamim was in Japan, South Korea, and China in early 2019 as well. Abu Dhabi’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed also did significant Asian travel that year, visiting Pakistan, China, South Korea, Singapore, Indonesia, and Malaysia. All of these trips represent deeper political ties, growing trade, and investment commitments.

The Strategic Logic

Beyond the importance of bilateral ties across regions, a larger strategic logic is at play. Gulf countries have long been diversifying their extra-regional partnerships to address regional security concerns. The more powerful countries with a deep interest in Gulf stability and share GCC preferences for regional order, the better. On the other side of the coin, Asian countries reliant upon Gulf energy are interested in regional stability. Political and diplomatic coordination with the status quo GCC is important in this regard.

Related to this is the perception of US retrenchment from the Middle East. Last summer’s pullout from Afghanistan fed into the widespread belief that the US is shifting its focus and resources away from the Middle East, which has occupied so much of its attention this century, and toward the “priority theatre” of the Indo-Pacific. The UAE’s presidential advisor Anwar Gargash expressed his views in the wake of the pullout: “We will see in the coming period what is going on with regards to America’s footprint in the region. I don’t think we know yet, but Afghanistan is definitely a test and, to be honest, it is a very worrying test.”

It is not only worrying for Gulf officials. Uncertainty about the US commitment would also affect many Asian countries that have thus far had minimal security presence in the Gulf. There have been steps toward security cooperation, albeit modest at this point. Beyond its recent missile deal with the UAE, South Korea has made in roads since signing the Barakah nuclear deal in 2009. South Korea’s international security activities remain a politically-sensitive issue, given its ongoing state of war with North Korea. However, it has developed some security ties in the Emirates built into the Barakah deal, including “a clause that guarantees the Korean military’sautomatic intervention in an emergency in the UAE.”

Defense and Security

Since 2011, it has also deployed an elite unit of specialforces – the Akh Unit – in the UAE that conducts joint training exercises and counter-terrorism training with its Emirati counterparts. Japan has also made limited moves in Gulf security. It has signed strategic partnership agreements with the UAE and Saudi Arabia, pledging to hold regular security meetings and cooperate on defense technology transfer. During then-PM Abe’svisit to the UAE, he pledged to deploy a Maritime Self-Defense Force destroyer to the Gulf, which he described as necessary because “thousands of Japanese ships ply those waters every year including vessels carrying nine-tenths of ouroil. It is Japan’s lifeline.”

India has also increased its military cooperation in the Gulf. It signed a Memorandum of Understanding on Defense Cooperation with Saudi Arabia in 2014, which resulted in a Joint Committee on Defense Cooperation. Italso has a Joint Military Cooperation Committee with Oman, India’s “closest defense partner in the Gulf.” India and the UAE also signed a strategic partnership agreement in 2017, with agreements on defense industries and cyber security signed.

Conclusion

As the world pins its hopes on a post-pandemic recovery phase, the GCC countries will increasingly become important actors in the Asianization process. Aside from the great power competition, we can expect tosee more engagement across Asia and the GCC on a wide range of issues.