最近,耶鲁大学校长彼得·萨洛维(Peter Salovey)在2017届毕业典礼上的演讲戳中了网友们的心。

他在演讲中说,在这个敲敲键盘就能跟几百人聊天的时代,我们却感到越来越孤独,人与人之间隔阂也在加深……

萨洛维的这一席演讲旁征博引,发人深思,值得好好精读一下。

首先,萨洛维对于当代美国人的“群体孤独”现象提出了担忧:

In the last thirty years, according to a recent article in Forbes, the number of Americans who report they have no friends - zero - has tripled. How can this be, when we can “friend” hundreds of individuals on social media with a tap of a finger?

《福布斯》杂志上的一篇文章说,在过去三十年里,一个朋友都没有的美国人的数量增长了2倍。在一个动动手指就可以在社交媒体上交到无数朋友的的时代,这怎么可能呢?

人们越是沉迷于社交网络,就越感到孤独。

The more one’s life is oriented around the Internet, the lonelier one tends to be. It is easier to email, text, and tweet than put away our smart phones and make a new friend with a living, breathing human.

人们的生活越是围着互联网转,他们就越感孤独。发短信、邮件、推特可比放下手机和一个活生生的人打交道简单多了!

但他表示,这个锅不能全让互联网来背。因为早在100多年前,这种现象就已经存在。

20世纪初,法国社会学家埃米尔·杜尔海姆(Emile Durkheim)曾提出过一种叫失范的现象(Anomie):

This is a sense of being unmoored or unconnected to social norms and institutions. The rise of industry, mass production, and the growth of cities were responsible for these feelings of disconnect.

这是一种和社会规范和社会体制脱轨的孤独感。工业的崛起、大规模的生产和城市的发展是人们产生这种脱离感的元凶。

unmoor:解缆;使拔锚

到了21世纪,社交媒体的兴起,使传统意义上的交流和纽带进一步被削弱。

他引用政治学家罗伯特·普特南生动的比喻:“独自打保龄球”(bowling alone),来描述当代社会传统社交结构的坍塌:

Putnam found that we are no longer a community of joiners; we no longer define ourselves by clubs and civic organizations that represent our hobbies and interests.

普特南发现我们不再是社区群体的积极参与者,我们不再通过代表兴趣爱好的俱乐部和组织来定义自己。

社会关系弱化了,人们又将何去何从?

How do we feel secure when we are no longer imbedded deeply in social networks or community groups? One possible outcome is that we retreat into ourselves.

当我们不再扎根于现实社交纽带或社区群体时,我们怎么才能有安全感?一个可能的结果是我们把自己封闭起来。

We may spend a lot of time staring into the mirror, attending only to information that is consistent with our preexisting beliefs. We focus on our own preoccupations. We become isolated and lonely.

我们可能会花很多时间盯着镜子,只关注与我们固有的信仰一致的信息。我们只专注和自己有关的事情,变成一个个孤独和孤立的个体。

这样,陌生人之间的隔阂就越来越深了……

Without community, without empathy, we cannot see ourselves in the eyes of the strangers among us. Instead, those strangers are at best ignored and at worst demonized.

没有社群、没有共情,我们无法从陌生人的眼中看到我们自己的模样。而那些陌生人对于我们来说,最乐观的情况是被无视,最糟糕的情况则是被妖魔化。

所以,我们有什么办法来拯救这个越来越孤独和异化的社会呢?

答案就是一个词:Empathy(同理心)。

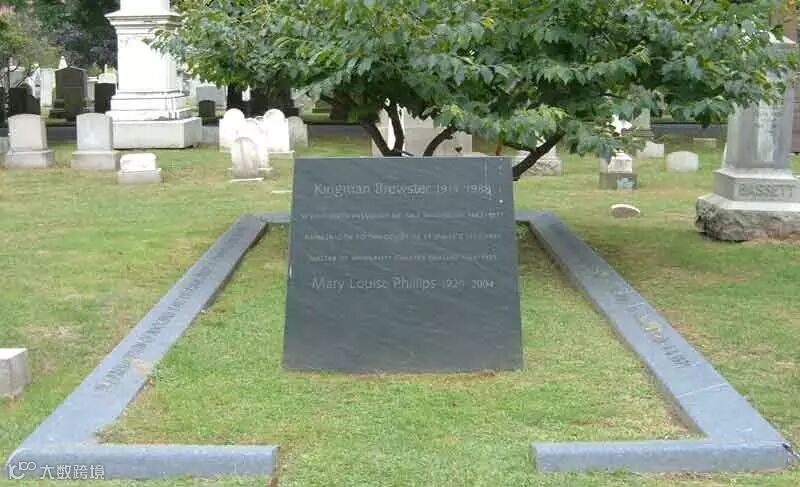

萨洛维提到耶鲁大学第17任校长金曼·布鲁斯特(Kingman Brewster)的墓志铭:要对陌生人慷慨,对他们抱有好的期望,而不是坏的期望。

他的墓志铭是这样写的:

“The presumption of innocence is not only a legal concept; in common law and in common sense, it requires a generosity of spirit toward the stranger, the expectation of what is best, rather than what is worst, in the other.”

“无罪推定不仅是一个法律概念,在法律和常识上,它都要求人们对陌生人展现出慷慨的精神,对他们抱有最好而非最坏的期望。”

对他人抱有最好的期待,这是布鲁斯特的常识:

Brewster was familiar with conflict; he knew how deeply people could disagree with one another, how fear and misunderstanding could divide them. Yet he expected the best in others: that was his common sense.

布鲁斯特了解冲突,他知道人们之间的分歧可以有多么深,他知道误解和恐惧可以怎样离间人们。然而,他对别人总抱有最好的期望,这是他的常识。

这也可以成为我们的常识,因为同理心是一个充满力量的工具(Empathy is a powerful tool)。

Ta-Nehisi Coates, the writer and social critic, has called for “a muscular empathy rooted in curiosity.” Such a muscular empathy should inspire us and spur us to action—to serve others and our communities.

作家和社会评论家Ta-Nehisi Coates曾呼吁人们都应当保持一种“基于好奇心的深深的同理心”。这种深深的同理心应激励我们采取行动,为他人和我们的社会团体服务。

他说,耶鲁大学的学生正是用这种心态在陌生人之间建立起了友爱的社群。他再度诵读起耶鲁校歌的歌词:

The seasons come, the seasons go,

The earth is green or white with snow,

But time and change shall naught avail

To break the friendships formed at Yale.四季更迭,云舒云卷

白雪皑皑,春意盎然

时间流逝,沧海桑田

耶鲁情谊,千金不换

最后,他激励毕业生们能够继续发扬耶鲁的精神,带着一颗同理心进入社会:

I urge you to take these experiences out into the world—a world that desperately needs your service, your curiosity, and yes, your empathy.

我敦促你们把这些经验带入世界——这个世界需要你们的贡献,你们的好奇心以及同理心。

I hope you identify with the plight of the other, walking a mile in the shoes of a stranger.

我希望你们理解他人疾苦,换位思考,穿着别人的鞋子感受一下。

By welcoming guests, by doing good to strangers, by knowing the hearts of others, you may well entertain angels.

热情好客,与人为善,体察人心,天使也会为你们动容。

怎么样,听了耶鲁大学校长的演讲,是不是觉得自己孤独的人生也不那么绝望了呢?

想练听力的同学可以再听一遍音频:

编辑:左卓

实习生:许凤琪