Methodology for System Complexity Analysis Based on the DIKWP Model (Extended Version)

Yucong Duan

International Standardization Committee of Networked DIKWP for Artificial Intelligence Evaluation(DIKWP-SC)

World Artificial Consciousness CIC(WAC)

World Conference on Artificial Consciousness(WCAC)

(Email: duanyucong@hotmail.com)

introduction

The vigorous development of artificial intelligence and cognitive systems is driving the innovation of algorithmic complexity analysis paradigms. Traditional algorithm complexity studies (such as time complexity, spatial complexity, etc.) mainly serve procedural or functional computing models, emphasizing single-dimensional indicators such as input-output, process control, and resource consumption. Although these classical complexity measures are effective in measuring the performance of algorithms, they cannot directly describe the semantic complexity and cognitive process complexity in the face of intelligent systems with semantic understanding and autonomous cognitive capabilities. For example, the current data-driven large language models (LLMs) have many limitations in terms of data, information, knowledge, intelligence, intent, and their mutual transformation: the lack of explicit characterization of "intent" will lead to incomplete, imprecise and inconsistent semantic content, opaque decision-making process, unpredictable results, and even potential ethical risks. This phenomenon shows that it is difficult to comprehensively measure the source and performance of system complexity in cognitive intelligence systems by relying only on traditional complexity indicators.

In order to solve the above problems, the researchers proposed the DIKWP model, which extends the complexity analysis to five semantic levels: Data, Information, Knowledge, Wisdom, and Purpose. The DIKWP model can be regarded as an extension of the classic DIKW (pyramid) framework, in which the representation of the "intention" (purpose/motivation) of the system is added on the basis of data-information-knowledge-intelligence, so that the goal-oriented behavior of the algorithm and the system can be quantitatively considered. This hierarchical semantic model can capture the structural elements of cognitive intelligence systems more comprehensively: the data layer focuses on objective perception, the information layer focuses on symbolic representation and pattern recognition, the knowledge layer embodies rules and associations, the intelligence layer involves decision-making and strategy, and the intention layer represents goal-driven and value judgments. Compared with the traditional planarized complexity model, DIKWP provides a layered, holistic, and semantic-oriented complexity expression framework. It not only allows the complexity of each layer to be measured separately, but also supports the analysis of the impact of semantic transformations between layers on the overall complexity, thus significantly enhancing the ability to characterize the complexity of AI systems.

It is important to note that the DIKWP model originally originated from the intellectual origins in the fields of knowledge management and cognitive science. As early as 1989, Ackoff et al. proposed the Data-Information-Knowledge-Intelligence (DIKW) hierarchy to describe the cognitive process by which raw data is processed and refined into information, then elevated to knowledge, and finally gives birth to wisdom. The DIKWP model inherits this hierarchical idea, and combined with the development of artificial intelligence, it adds a focus on "intention" to meet the modeling needs of goal-oriented behavior in autonomous agents. Duan Yucong and other scholars further put forward the theory of "Relation Defines All Semantics" (RDXS), which expands the traditional knowledge graph into an interrelated five-layer semantic graph (data graph, information graph, knowledge graph, wisdom graph, and intention graph) with the help of the DIKW conceptual system, which can map incomplete, inconsistent and imprecise subjective/objective cognitive resources in reality. This indicates that the DIKWP model has a unique advantage in expressing the uncertain semantic relationship of complex systems, and can provide strong support for the semantic modeling of artificial consciousness systems. In the interaction scenario of artificial consciousness and advanced cognition, the DIKWP model is helpful to realize the effective mapping of the subjective internal cognition and objective external expression of the interactive subject. By building a problem-oriented and intent-driven technical framework, the DIKWP methodology can alleviate the problem of opaque AI decision-making process and realize the visualization and explainability of human-computer interaction. This is critical for building bidirectional explainable, trustworthy AI systems, highlighting the potential of the DIKWP model to meet AI ethics and governance requirements.

In summary, this article will be a comprehensive extension of the existing simplified content. Focusing on the core case of artificial consciousness and cognitive intelligence system, we will systematically discuss the complexity analysis methodology of the DIKWP model, including: (1) demonstrating the advantages of the DIKWP model in the modeling of cognitive intelligence system and its enhancement effect on complexity expression; (2) Explain in detail the definition and connotation of each layer of DIKWP (data D, information I, knowledge K, wisdom W, and intention P), derive the complexity calculation formula, and give the theoretical basis and typical metric indicators; (3) analyze the complexity introduced by the interaction between layers, and establish a mathematical model to characterize the evolution of the overall complexity; (4) Introduce at least three instance scenarios (such as AI education system, autonomous unmanned system, and multi-modal large model platform) to analyze their complexity performance characteristics and optimal control paths in each layer of DIKWP; (5) Introduce cutting-edge concepts such as semantic elasticity, relative complexity of subjects, and semantic space circulation, and construct corresponding quantitative analysis frameworks to incorporate them into the complexity evaluation system; (6) Discuss the integration of DIKWP method with current mainstream AI frameworks (including Transformer large model, reinforcement learning paradigm, multi-agent system, etc.); (7) Combining the perspectives of cognitive science, complex systems theory, computational neuroscience and other fields, the multidisciplinary connection of DIKWP complexity analysis is established. Through the expansion of the above contents, this paper hopes to form a complexity analysis system with rigorous structure, sufficient citations and cutting-edge academic value, which will provide a scientific reference for the theoretical research and engineering practice of artificial consciousness and cognitive intelligence systems.

Overview of the DIKWP model and modeling advantages

The DIKWP model divides the intelligent system into five layers of data, information, knowledge, intelligence, and intention according to the semantic abstraction level, and each layer performs its own function and is interconnected with each other, forming a semantic network of gradual abstraction. The data layer (D) corresponds to the objective data of the original sensory input or recording; The information layer (I) is the representation of data after it is structured and given semantics; The knowledge layer (K) contains rules, concepts and their associations, which constitute the knowledge base of the system; The intelligence layer (W) involves the ability to make global planning, dynamic decision-making, and strategy selection based on knowledge; The intent layer (P) represents the purpose, intent, and value orientation of the system. In this model, the lower layer provides the foundation and support for the upper layer, and the upper layer constrains and guides the lower layer, and the five layers together form a complete cognitive computing framework. Through the hierarchical characterization of DIKWP, we can adopt different complexity measures for different levels, so as to obtain a panoramic understanding of the complexity of the system.

It is worth emphasizing that the DIKWP model has significant modeling advantages and complexity expression capabilities. First, the hierarchical structure allows complex systems to be disassembled into smaller subsystem blocks, and there are far more high-frequency interactions within each layer than between layers, forming a "nearly decoupled" architecture. This is similar to what Herbert Simon describes as a "near-decomposable" system structure – subsystems are tightly coupled internally and communicate only externally through a limited number of interfaces, a hierarchical architecture that greatly reduces the overall complexity of the analysis. Specifically, under the DIKWP framework, we can measure the complexity of different stages such as perception, cognition, decision-making, and intention, avoiding the embarrassing situation that the traditional single indicator is difficult to take into account the multi-layer confounding phenomenon. For example, for highly complex agents such as artificial consciousness systems, the DIKWP model provides a complete semantic chain from sensory input to goal planning, enabling researchers to quantify system behavior from multiple perspectives such as data statistics, information entropy, knowledge relevance, decision-making complexity, and intention diversity. At the same time, the explicit division of semantics at each level helps to locate the source of complexity: we can clearly distinguish whether the explosion of perceptual data is causing the increase in complexity, or the exponential increase in the combination of decision-making solutions is causing the complexity bottleneck, and take targeted optimization measures accordingly.

Furthermore, the DIKWP model shows a strong ability to deal with uncertainty semantics. Traditional knowledge graphs mainly cover explicit entity relationships, but the introduction of the intent layer allows subjective factors to be included in the modeling category. The RDXS semantic model proposed by Duan et al. shows that the knowledge graph can be extended into a five-fold graph system including data, information, knowledge, wisdom, and intention with the help of DIKWP structure, which is used to map multi-sourced, incomplete and inconsistent subjective and objective resources in the real world. This mapping method enables the system to represent and fuse noisy, fuzzy, and conflicting information at the semantic level, thereby resolving uncertainty. For example, if there are inconsistencies between data from different sources, the information layer can find out the conflict points through topological association, the knowledge layer can standardize and correct according to logical rules, and the intelligence layer can adjust the decision-making strategy accordingly, and finally evaluate which scheme is more in line with the purpose and value orientation of the system at the intention layer. This bottom-up purification and top-down constraining process enables the system to maintain semantic consistency and decision-making reliability in a complex and changing environment. This is especially true in the context of artificial consciousness: the DIKWP model provides a platform for two-way mapping between subjective consciousness content (such as goals and preferences) and objective environmental information, and the machine can disassemble the vague high-level intentions of humans into executable low-level operations, and at the same time, it can also generalize and promote the low-level massive data into high-level knowledge that is meaningful to humans. This two-way explainability is an important feature of the next generation of human-machine integrated intelligent systems.

Figure 1: Schematic diagram of the mapping of subjective and objective resources of multi-source imprecision, incomplete, and inconsistent human-machine-object interaction to the semantic graph of each layer of DIKWP. The diagram shows how to transform the chaotic and diverse raw resources into structured data graphs, information graphs, knowledge graphs, wisdom graphs and intention graphs through the processes of data clustering, information topology association, knowledge logic specification, wisdom value quantification and intent functionalization. In this process, a large number of low-level details are abstracted by high-level concepts, and semantic information is gradually propagated and fused between levels: the clustering of the data layer compresses the scale of massive raw data, the topological association of the information layer transforms the data pattern into a relational network, the logical specification of the knowledge layer further generalizes the information into inferential knowledge rules, the intelligence layer evaluates the value of knowledge to select the best strategy, and the intention layer finally puts the strategy into functional goal execution. Through the above graphical representation, cross-level semantic flow and uncertainty processing are realized, and the complexity of the whole system can be effectively represented at different abstraction levels.

In summary, the DIKWP model lays a new foundation for analyzing the complexity of intelligent systems through clear hierarchical division and semantic integration. The following is an in-depth analysis of each layer, and the definition, formula derivation, theoretical source, and practical indicators of the complexity of each layer are given to build a comprehensive complexity measurement system.

DIKWP Layer Complexity Measurement

Layer D: Data complexity

Definition: The data layer corresponds to the original set of data perceived by the system, including sensor readings, raw input signals, log records, and other lowest-level information carriers. The complexity of this layer reflects the amount of raw data and the size of the data dimensions that the system needs to process per unit of time. Intuitively, the complexity of the data layer depends on the size of the data and the sampling rate: the larger the number of data points and the faster the generation rate, the higher the complexity of the data layer processing. For example, in a visual perception system, the large number of pixels per second generated by a high-definition camera creates a direct complexity challenge for subsequent processing.

Typical metrics: The total number of data points, data dimensions (such as the feature length of each data point), sensor sampling frequency, etc., are all direct indicators of data complexity. Estimating the size of the raw input to a data layer in terms of (number of data points) is a common and valid method. If the system needs to process raw data points per second, the data layer complexity can be considered to be proportional to N in magnitude.

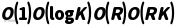

Complexity Formula: In common cases, data layer complexity can be expressed as:

,

,

That is, linearly proportional to the number of data points. This means that if the amount of data that the system needs to process doubles, the computational resources (such as time) consumed by the data layer will roughly double. For example, if the camera sensor of an unmanned vehicle collects 640×480 resolution video images at a rate of 30 frames per second, the number of pixel data points generated per second is about . As a result, the original input complexity of the data stream is about 10 million data points per second. Such a large N poses a severe test for real-time systems, which need to be efficiently optimized in hardware and algorithms.

Theoretical Sources and Analysis: The complexity of the data layer basically follows the measurement method of input size in classical computational complexity theory. In algorithmic analysis, the time complexity is usually expressed as a function of the input scale n; Corresponding to the data layer of the intelligent system, n can be analogous to the number of data points N. For example, if you do a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) for a time series signal with a length of M, the complexity of the algorithm is, but from the perspective of the data layer, we can also consider that the number of data samples to be processed is M, so the data size M is still the dominant factor in complexity. In other words, the data layer complexity metric emphasizes the growth trend in quantity, and has less to do with the specific type of operation performed, and more concerned with how much data needs to be "touched". For example, if a dataset of N pixels is processed pixel-by-pixel, the lower bound of time complexity will increase linearly with N without further optimization, i.e., regardless of the operation performed on the image (filtering, compression, or simple traversal), i.e. This is a striking feature of data layer complexity: it is directly controlled by the size of the data.

However, in a real-world system, data layer complexity can also be affected by data dimensions and structure. For example, high-dimensional data (e.g., hundreds or thousands of features per point) may require more operations to process, resulting in an actual complexity of (where d is a dimension). In addition, the way the data is organized (e.g., whether it is stored in continuous memory, whether it is sorted) can also affect the constant factor or even the order. Overall, however, the cornerstone of the complexity analysis of the data layer is still an order of N inputs. In the DIKWP methodology, we focus on the data layer mainly to obtain a lower bound estimate and starting point of the complexity of the entire system: if even the original data is too large to read, there is no way to talk about the subsequent layer. Therefore, in many optimizations, reducing the complexity of the data layer is the primary strategy, such as reducing redundant data collection, using lower data resolution, and pre-filtering of data, so as to make N as small as possible and control the complexity scale from the source.

Layer I: information complexity

Definition: An information layer represents a meaningful representation of patterns, features, or symbols extracted from raw data. "Information" here refers to the intermediate results that have been processed and interpreted, such as the feature vector formed by feature extraction of the sensor signal, the information unit obtained by word segmentation and grammatical analysis of the original text, and the target list obtained by image recognition. The complexity of the information layer reflects the computational complexity and multi-source fusion difficulty required in the process of transforming data into information. The main factors affecting the complexity of information include the cost of the feature extraction algorithm (linear, log-linear or higher complexity), the depth of multi-channel information fusion (whether it is necessary to combine information across modalities or sources), and the complexity of event composition (the combination of multiple independent events or signals needs to be considered at the same time). The information layer actually acts as a transition zone from "data to knowledge", and its performance in complexity inherits both the impact of data size and the complexity of the algorithm itself.

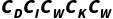

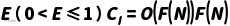

Typical metrics: The number of basic operations or features that need to be performed to extract information from N data points is represented by symbols, and the complexity of the information layer can be regarded as an increasing trend. Common metrics include: feature number (the number of meaningful features extracted), pattern type (pattern type/event type recognized), number of fusion channels (number of data sources participating in information fusion), etc. For example, in computer vision, if edge detection is performed on an image of a pixel, the typical number of operations is proportional to the number of pixels, ie. Another example is to perform spectral transformation (such as FFT) on a voice signal of length M, and the operation complexity is about . These indicators reflect the complexity function of the information processing algorithm with respect to the data scale N.

Complexity Formula: Information layer complexity can generally be expressed as:

,

,

where is some kind of function that does not exceed the polynomial growth. Ideally, feature extraction or information transformation algorithms should not be more complex than linear or linear logarithms (otherwise it would be difficult to be real-time in the face of big data). In many cases, close to or. For example, the complexity of the image edge detection algorithm described above is (equivalent to a constant number of operations per pixel); The complexity of the fast Fourier transform of a speech signal is . More generally, if we extract F features from N pieces of data, the usual form can describe the growth of the number of features with the amount of data, where α≤1 corresponds to linear or sublinear extraction, and α>1 means that more and more information features are derived per unit of data (this is less common in fine analysis, but can occur in the case of multiple combinations of features).

It should be noted that it also depends on the need for information fusion. When the system needs to fuse the content of multiple data sources into comprehensive information, the complexity may increase as a product rather than simply additive. For example, in multimodal information fusion, suppose there are two sensor data streams, each producing N1 and N2 pieces of data, and if you need to match each piece of data to each other, the worst-case complexity is required. However, it is usually possible to reduce the computational effort of fusion through feature filtering and association matching algorithms. For example, only the window matches in time, or the high-level features are extracted separately and then matched, so as to avoid exhaustive combinations.

Theoretical Sources and Analysis: The complexity of the information layer is affected by both the information theory and the complexity theory of pattern recognition algorithms. On the one hand, according to Shannon's information theory, the entropy of the information contained in each piece of data determines the upper limit of extracting useful information. If the data is very redundant or noisy, the computational effort required to extract meaningful information can be more complex because the signal needs to be separated from the noise. On the other hand, from the perspective of algorithms, various feature extraction and pattern recognition algorithms have their own complexities: for example, the computational complexity of convolutional neural network (CNN) to extract image features is related to the size of the convolutional kernel, the depth of the network and the size of the image; The decision tree summarizes the information pattern from the data, and its construction complexity is related to the product of the data dimension and the number of samples. The complexity of information extraction mined by association rules can grow exponentially (in the worst case) with the size of the data. The complexity of these algorithms is directly reflected in the information layer. Therefore, the analysis of the complexity of the information layer needs to be combined with the specific information processing method and the form of evaluation.

In practice, a rule of thumb is that moderate information preprocessing can be achieved at a small cost in exchange for a significant reduction in complexity in subsequent layers. In other words, the time spent or time behind the data layer to extract refined information features tends to reduce the burden of exponential search or highly complex reasoning at the knowledge and intelligence layers. Therefore, the information layer is often regarded as a "complexity control valve": we want to optimize the feature extraction algorithm to keep the C_I as low as possible, but we need to ensure that the extracted information is comprehensive enough to support subsequent decisions. Typical optimization measures include the use of fast signal processing algorithms (e.g., FFT, fast filtering), dimensionality reduction techniques (e.g., PCA to reduce the number of features), feature selection (elimination of redundant or related features), and hierarchical fusion strategies in multi-sensor information fusion (step-by-step fusion rather than fusion of all sources at once). By doing so, it is possible to reduce the growth rate while maintaining the amount of information, thereby optimizing the complexity of the information layer.

Layer K: Knowledge complexity

Definition: The knowledge layer corresponds to the structured knowledge base owned by the system, including symbolic knowledge (e.g., rules, facts), statistical knowledge (e.g., probabilistic model parameters), and modeled experience (e.g., weights learned in machine learning models). The knowledge layer is the link that connects information and wisdom: it inherits the symbols refined by the information layer, and the reasoning and decision-making of the intelligence layer is initiated below. The complexity stems from the cost of storing, retrieval, and reasoning in a vast knowledge space. Typical knowledge-layer tasks include: retrieving relevant entries from the knowledge base, making logical deductions based on knowledge, invoking existing models for inference, and so on. The complexity of these tasks often depends on the size of the knowledge (the number of elements in the knowledge base) and the structure of the knowledge organization (e.g., whether there is an efficient index, whether exhaustive search is required).

Typical indicators: If K pieces of knowledge (such as K facts, rules, or concepts) are stored in the knowledge base, and R-related rules or queries need to be considered when reasoning or matching, the complexity of knowledge layer operations is typically related to K and R. It can be used to represent the number of knowledge items that need to be checked during a retrieval/inference process, and the total size of the knowledge base. Other metrics include the relevance of knowledge (how many other knowledge each piece of knowledge is linked to on average), the branching factor of knowledge query (how many sub-inference branches need to be split into a single inference), etc. These metrics affect the search complexity of the algorithm in the knowledge space. For example, an unoptimized knowledge retrieval requires traversing K record matching conditions, then; If a hash index is used, the average can be reduced to a constant or logarithmic scale; The complexity of the association query based on the knowledge graph is related to the node degree and graph diameter. In logical reasoning, if there are R rules that need to try to match K facts, the worst-case combinatorial complexity is. Therefore, sum is a basic quantitative indicator to capture the complexity of the knowledge layer.

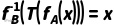

Complexity Formula: For the knowledge layer, the following complexity expression can be given:

,

,

where K is the storage scale of the knowledge base, and R is the number of knowledge items involved in retrieval or inference. In the most naïve case, it may be necessary to match the R rule to the K knowledge one by one, so the complexity is productive. However, most knowledge operations can be significantly optimized by introducing appropriate data structures and algorithms. For example, using a hash table or a balanced tree to store knowledge can reduce the complexity of a single retrieval to or, making it close. Another example is pattern matching based on inverted indexing, which can avoid traversing the entire knowledge base and only need to directly locate candidates for phase keys, thus greatly reducing the actual size. Therefore, the above equation gives more like the upper bound complexity of knowledge operations; In the actual system, structured storage and pruning strategies are usually between sublinear and linear.

In order to illustrate the source of knowledge complexity, consider two extreme cases: one is a flat and unordered knowledge base without any indexing aid, then retrieving a certain knowledge requires an average of K records, and in this case, if the R rule is to be applied to the reasoning, an R×K match check must be performed, which is the worst-case scenario. The second is a highly indexed and well-organized knowledge base, for example, if the hash or B-tree index Facts is used, then the average of the relevant knowledge is or , then the complexity of the process of applying the R rule is about, which is almost independent of the total size of the knowledge base. These two cases define the upper and lower bounds of the complexity of the knowledge layer. The reality lies somewhere in between: knowledge is often partially organized through hierarchical categories, map links, etc., but still requires a certain range of searches. In addition, combinatorial explosion problems can arise in knowledge reasoning, where the combination of certain rules with each other may produce exponentially new knowledge, especially in logical derivation (e.g., theorem proof, constraint solving). In fact, in computational complexity theory, generalized logical reasoning is proven to be NP-complete, and many inferences involving knowledge inevitably face exponential complexity in the worst-case scenario. For example, the reasoning problem of first-order predicate logic is semi-decidable (there is no universally valid polynomial algorithm); The propositional logic satisfiability problem (SAT, formally a form of intellectual reasoning) is NP-complete. These complexity results remind us that once the knowledge layer is involved in complex combinatorial reasoning, it can be much more complex than simple models. However, in DIKWP complexity analysis, we focus on common operations and averaging cases, limiting the complexity to the polynomial range to make the analysis meaningful.

Theoretical Source and Analysis: Knowledge layer complexity is closely related to database retrieval theory and logical reasoning complexity theory. In terms of database retrieval, various index structures (such as B-trees, hash indexes) and query optimization techniques are designed to reduce the complexity of data retrieval. In the field of knowledge representation, graph structures (such as semantic webs and knowledge graphs) provide a way to narrow the search scope by using local adjacencies, so that the query complexity depends more on the local degree of the graph than on the global scale. This can be seen as keeping it within a relatively small range, thus avoiding the occurrence of direct rides. At the same time, in the research of expert systems and reasoning machines in artificial intelligence, people use methods such as forward chain reasoning, reverse chain backtracking, and heuristic search, which are also to deal with the complexity of knowledge reasoning. For example, the well-known heuristic algorithm can reduce the search complexity from exponential to close to polynomial, which is equivalent to using knowledge (heuristic functions) to guide the decision-making of the intelligence layer, thereby reducing the number of branches to be considered in the knowledge layer in advance.

When actually building intelligent systems, we often reduce complexity through knowledge compression and reduction: this includes removing irrelevant or redundant knowledge, merging duplicate rules, or hierarchically organizing knowledge to reduce the domain covered by each inference. For example, in the medical diagnosis expert system, the medical knowledge base is divided by specialty, and if the problem belongs to the category of heart disease, there is no need to load the knowledge of dermatology, so as to effectively narrow it down. Or use knowledge distillation technology to condense large knowledge models into smaller models to reduce the cost of inference. These measures are essentially to reduce the search space of the knowledge layer and ensure that it remains in a controllable range.

In conclusion, the complexity of the knowledge layer reflects the difficulty of efficient search and reasoning in a large knowledge space. Through rational data structures, algorithms, and knowledge organization, we strive to make the complexity of the knowledge layer increase approximately linearly with the size of the task, and avoid exponential loss of control due to combinatorial explosion. The introduction of the DIKWP model enables us to clearly focus on the position of the knowledge layer in the overall system complexity and apply the corresponding optimization strategies.

Layer W: Intelligence complexity

Definition: The intelligence layer represents a system's ability to leverage knowledge for global planning, dynamic policy development, and complex decision-making. This layer involves putting knowledge into practice and choosing the best course of action in a changing environment. The complexity of the intelligence layer is mainly due to the size and structure of the decision-making space: the number of possible states, the number of actions to choose from in each state, and the depth of steps that need to be considered to achieve the goal. To put it simply, the intelligence layer needs to search for a solution (or approximate solution) that satisfies the target in a huge solution space, and its complexity is closely related to the size of the state space and the efficiency of the search/planning algorithm. In addition, the existence of multi-objective decision-making (which requires trade-offs between multiple objectives) or dynamic policy adjustments (where environmental changes prompt policies to be updated in real time) can significantly increase the complexity of the intelligence layer.

Typical metrics: A is about or (without pruning) if the possible state space size of the system (number of states), A is the average branching factor of the state, and D is the depth of steps involved in the decision scheme. Commonly used metrics to measure the complexity of the intelligence layer include the size of the state space, the branching factor (the number of possible actions per state), the depth of planning or the length of the decision chain, and the number of policy generation. where S is an overarching indicator that reflects the scale of the problem itself; Rather, it represents the number of different policy scenarios that are generated and evaluated in a multi-policy scenario. For example, in a path planning problem, the state space can be the total number of possible location nodes on the map, the number of directions that each location may move, and the length of the path steps. For example, in a chess game, S is equivalent to the total number of possible games, the number of choices that can be made for each move, and the level of the number of moves that are expected to be searched.

Complexity Formula: For the intelligence layer, complexity can be approximated as

,

,

If it is assumed that the planning/decision-making algorithm can make efficient use of knowledge constraints, the decision is limited to the relevant state subspace. But in general, you need to consider situations where you might build and evaluate a policy multiple times, which can be scaled to

,

,

where G is the number of times the policy was generated or evaluated. For example, if the system needs to compare different planning scenarios, each of which involves traversing a state space on an S-scale, the total complexity is multiplied by a factor. A concrete example: in a path planning problem with a map size of 1000×1000, the state space is maximum. The heuristic A algorithm is used to find the complexity of a single path of the same order, that is, the magnitude. If you need to try to make trade-offs between multiple strategies such as obstacle avoidance, shortest circuit, and energy optimization (assuming a combination of different weights), you may perform multiple plans, and the total complexity will be approximately increased.

Of course, in decision planning, the actual complexity is strongly related to the efficiency of the algorithm. Heuristic algorithms, pruning strategies, hierarchical planning, etc., can greatly reduce the number of nodes actually searched, so that the number of effectively explored states is much smaller than that of theoretical S. Ideally, a well-performing intelligent layer algorithm will control the number of states that need to be evaluated to be linearly related to the size of the problem, so it can be seen as such. However, in the worst-case scenario or in the absence of good heuristics, the search may have to traverse most or even all combinations of states, exponentially exploding in complexity (e.g., decision tree complexity at exhaustive depth D). Therefore, the above formula can be understood as two estimates, ideal and general: assuming adequate pruning and heuristics, and taking into account possible multi-strategy attempts.

Theoretical Sources and Analysis: The theoretical basis of the complexity of the intelligent layer is derived from the artificial intelligence search algorithm and combinatorial optimization theory. In AI, the complexity of planning and decision-making problems has been studied for a long time: classic results such as the Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP) are NP-difficult, the complexity of chess games is beyond the scope of feasible searches, and so on. These suggest that the complexity of the intelligence layer may be exponential for general complex decision-making tasks. However, by introducing domain knowledge (from the knowledge layer) and heuristics, we can often limit the actual search to a smaller subset of the exponential space. A typical example of this is the algorithm: using heuristic functions, the number of nodes that need to be scaled is drastically reduced to the number of states that the true optimal path passes, without having to traverse the entire graph. Under good heuristics, the time complexity is close to linear to the state number S. Another example is Monte Carlo tree search, in which the search work of the giant game tree is limited to the most promising branches through random simulation and evaluation pruning in game decision-making. Similarly, the dynamic programming approach polynomializes the exponential problem by reusing the subproblem solution, which can be seen as using intelligence (algorithmic strategy) to reduce the effective state space. In short, a series of approaches in the field of AI decision-making are all about countering the complexity of intelligence layer problems.

The DIKWP framework highlights the constraining effect of the knowledge layer on the complexity of the intelligence layer: knowledge can constrain the decision search to a certain extent, so that the complexity of the intelligence layer can be controlled. If the knowledge layer provides perfect rules and models, the wisdom layer can directly deduce decisions based on knowledge without blind search, and the complexity is greatly reduced. On the contrary, if there is a lack of knowledge, the intelligence layer has to conduct large-scale searches to fill the knowledge gaps, and the complexity increases dramatically. This is reflected in the trade-offs between the W/K layers: if there is sufficient knowledge, the wisdom search will be simplified, and if there is insufficient knowledge, the wisdom complexity will increase. Therefore, when designing agents, it is common to reduce the state space that the intelligence layer needs to explore by adding knowledge (such as adding a rule base or training an empirical model).

Another source of complexity for the intelligence layer is multi-objective coupling. When a system is faced with multiple goals at the same time (e.g., an autonomous vehicle needs to take the shortest route while avoiding danger and saving energy), the intelligence layer must consider the goal trade-offs when generating policies. This adds another dimension to the decision-making space, requiring switching between different target strategies or evaluating them in parallel. If not handled properly, it can lead to a spike in portfolio complexity. Generally, the multi-objective optimization theory can be introduced to transform the multi-objective problem into a series of single-objective problem solving through weighted sum, hierarchical optimization, etc., so as to avoid exponential complexity. For example, there are two phases of planning: the first phase satisfies hard constraints such as safety, and the second phase optimizes the path length or energy source while satisfying the results of the first phase. In this way, the big problem is disassembled, and the actual complexity is the sum of the complexity of the sub-problems, not the product.

In order to suppress the complexity of the intelligence layer, we have several entry points: one is pruning and heuristics, which use domain knowledge to reduce useless searches; The second is hierarchical decision-making, which distinguishes long-term goal planning from local immediate response, and plans for their own small problems in a hierarchical manner. The third is parallel search, which uses multi-threading or multi-agent to explore different parts of the space at the same time to speed up the search (but this is equivalent to increasing the parallelism of resources rather than reducing the progressive complexity in complexity analysis). In addition, the learning strategy is also one of the trends, that is, using machine learning to train an approximate decision model in the offline stage, which approximates the output of the decision at runtime in constant time, thereby greatly reducing the online complexity. However, the training itself is costly, and there is a trade-off between overall efficiency. In the DIKWP framework, the complexity analysis of the intelligent layer reminds us that decision-making problems are often one of the main bottlenecks of complexity, but it is precisely the introduction of innovative algorithms and structures at this layer that can produce qualitative efficiency improvements.

P-layer: intent complexity

Definition: The intent layer represents the set of goals, task planning, and subjective intentions pursued by the system. It is at the top of the DIKWP architecture and dictates the direction of the system's behavior. In a single-task environment, the intent may be fixed (e.g., navigating to a specified destination); However, in complex multitasking environments or interactive scenarios, intent may change dynamically or be negotiated across multiple subjects. The complexity of this layer comes from the complexity of target switching, task scheduling, and intent coordination. Additional complexity overhead is introduced when a system needs to change its goals during operation, when it is necessary to choose between multiple tasks, or when multiple agents need to coordinate their own intentions. This includes re-planning new goals, computations for allocating resources across different tasks, and dealing with the costs of multi-objective conflicts and consistency.

Typical metrics: T is used to denote the number of intent/task switching during the operation of the system, and L is the number of replanning or feedback adjustment cycles that accompany each switching (i.e., the length of iterative process required to accommodate the new intent). In addition, in a multi-agent or multi-task environment, metrics such as the size of the intent space (the number of possible different target kinds) and the degree of intent coupling (the strength of the goal association between different subjects or tasks) can be defined. Together, these metrics affect the complexity of the intent layer: frequent target switching (large T), complex adjustment process (large L), or multiple goals that are highly correlated and need to be repeatedly coordinated will increase the complexity of the intent layer.

Complexity Formula: The intent layer complexity can be expressed in the following form:

,

,

where T is the number of intention changes and L is the number of feedback adjustment cycles involved in each adjustment. Intuitively, if the system always runs around a single goal (T≈1, no switching), then the intent layer only introduces complexity once when the goal is initially set, and does not increase the burden later. However, if the system needs to switch frequently between different goals/tasks (e.g., multitasking, interactive dialogue system constantly changes goals according to user needs), each DIKW layer needs to be adjusted accordingly, and the cost is proportional to the switching frequency T. The number of feedback loops required for each intent adjustment, L, reflects the length of the iterative process required to converge on a new goal. If the adjustment process requires multiple rounds of information collection-decision-evaluation feedback loop (e.g., the autonomous system repeats trial and error under a new task to calibrate the strategy), the L is larger and the complexity increases accordingly.

For example, a smart home assistant manages both security and energy optimization goals. When an intrusion event is detected, it needs to temporarily switch intent to prioritize security (T increases by 1); After the event is over, switch back to daily energy optimization (T plus 1). Each time an intent is switched, it needs to re-plan the scheduling of sensors and devices (e.g., mobilizing cameras, pausing air conditioning, etc.), which may involve several feedback loops to stabilize the new state (assuming each time). Then, if T = 2 switches occur over a period of time, the total intent layer complexity may be about (only a rough count is made here). For example, when a multi-agent UAV formation performs a mission, the local intent of each UAV needs to be coordinated with the global mission intent. If the formation or division of tasks is adjusted every once in a while, which is equivalent to a global intent reorganization, then depending on the number of team members and the coordination algorithm, each reorganization may require a certain iteration of communication (L) to reach a consensus intent. Frequent restructurings or large-scale collaborations can drive up the complexity of the intent layer.

Theoretical source and analysis: The intent layer complexity can be understood from two perspectives: task scheduling theory and multi-agent planning. In the context of single-system multitasking, the intent to switch is similar to the process switching of the operating system, and frequent context switching will bring overhead (increased complexity). The scheduling theory shows that in the hard real-time system, frequent task switching increases the complexity and system overhead of the scheduling algorithm, which is consistent with the view that C_P increases with T. Similarly, if the task switch involves recovery and cleanup of the context (equivalent to a feedback loop adjusting the system state), an extra step L is introduced. Therefore, the ** form can also be regarded as the quantification of additional complexity caused by task switching.

In multi-agent collaboration, distributed planning and consensus algorithms study the complexity of multiple agents coordinating common goals. For example, reaching a consensus intention (consensus) for multiple agents often requires iterative information exchange. The complexity of the classical consensus algorithm is related to the network topology and the number of iteration rounds: it usually takes rounds of communication to make all the subjects' intentions agree or converge to a certain error range. Therefore, if a multi-agent system frequently needs to re-agree on different tasks, it will also be amplified. To make matters worse, when there is a conflict of intent between the parties, the negotiation or game process itself may be exponentially complex (e.g., the general multi-party game equilibrium problem). However, in the DIKWP framework, we tend to classify this part of the complexity into the game decision complexity of the intelligence layer, while the intent layer mainly describes the frequency of switching and scheduling.

The role of the intent layer in overall complexity can be understood in this way: it is equivalent to the "top-level control logic" of the system. If the top-level control logic is stable and clear (almost unchanged goal), the system can be optimized in one direction for a long time, and the complexity of each layer tends to be stable. If the top-level logic keeps changing direction (changing targets frequently), then it is tantamount to making the system "keep restarting new problems", and the accumulated complexity is similar to the number of switches. This kind of overlay sometimes even causes additive loss due to interference between the old and new targets, which is manifested as a higher complexity than linear increase (e.g., frequent switching leads to invalid cache, learning forgetting, and needs to be compensated for at an additional cost). Therefore, a common approach in engineering is to reduce unnecessary switching, maintain intent stability, or set up meta-scheduling at a higher level (reducing the actual frequency of switching) to reduce the complexity introduced by the intent layer.

In general, the intent layer complexity emphasizes the cost of the macro-control process of the system. With proper task planning and intent management, the number of goal changes can be minimized, and the transition when changing is fast and smooth (reducing the number of feedback iterations C_P) can be kept to a low level. For example, predictive scheduling allows the system to switch tasks in a planned way instead of randomly, or continuous learning allows the system to partially follow an existing strategy when switching targets (reducing the number of readaptation cycles). These strategies can be thought of as optimizing at the intent layer, which indirectly improves the complexity performance of the entire system.

Interlayer coupling complexity and global evolution model

The complexity analysis of the above layers is relatively independent, but in the actual system, the layers of DIKWP do not operate in isolation, but form an organic whole through interactive coupling. The output of one layer often becomes the input of the previous layer, and there are feedback loops and bidirectional effects between layers. This interlayer coupling may result in a different behavior from the simple addition of layers: it may be higher than the linear superposition of the complexity of each single layer (with synergistic gain or additive loss), or it may be lower than the simple additive (with mutual cancellation or efficiency improvement) due to the mutual constraints between the layers. Therefore, it is necessary to build a model to describe the evolution of the overall complexity of the system and understand how the interlayer coupling changes the magnitude of the complexity.

First, you can try to estimate the overall complexity in terms of macro aggregates. Assuming that the computational costs of each layer can be superimposed during a complete operation of the system, a preliminary upper bound estimate can be obtained by adding the complexity expressions of the above layers:

.

.

This is equivalent to assuming that the layers are executed sequentially and without significant duplication or mutual exclusion – each layer of complexity contribution comes at an additional cost. As previously derived, . Adding these up directly may result in a fairly high upper bound for complexity. However, this simple addition does not take into account interlayer relationships, such as the work of one layer may reduce the workload of another. A more complex, but more practical, approach is to consider couplings: the interaction of layers I and J creates additional complexity, or reduces complexity with each other. The coupling coefficient can be introduced to represent the complexity effect introduced by the interaction of layers I and J, and the overall complexity can be expressed as:

,

,

where represents the complexity of the first layer itself (in DIKWP order) and is a function that describes the complexity of the interaction between layers i and j, which may take a simple product, linear, or more complex form. is the weight coefficient, which reflects the strength and type of coupling. If the coupling of layers i and j would introduce additional complexity, then the corresponding λ is positive; Conversely, if the coupling leads to efficiency improvement and reduced complexity, λ can be taken as a negative value.

For example, the knowledge layer (K) and the intelligence layer (W) are often positively coupled: knowledge guides decision-making, and decision-making feeds back new knowledge. In the positive and benign case, the rich knowledge base makes the intelligent layer planning more effective (equivalent to negative value, and the overall complexity is reduced); However, if there is ambiguity or conflict in knowledge, the intelligence layer will have to spend an additional cost to screen (which is a positive value and increases the complexity). Another example is the relationship between the data layer (D) and the information layer (I): high-quality data (high complexity of layer D) can reduce the difficulty of information extraction (the complexity of layer I decreases), which is manifested in the fact that although it increases, it decreases, and the two partially cancel each other. Expressed as a coupling term, i.e., negative, offsets a portion of the value. This offset exists in many systems: more data points N (increase) can reduce uncertainty through statistical averaging, thus simplifying information extraction (reduction). Conversely, if the data redundancy is too high, the information layer has to perform a deredundancy operation, causing the C_I to rise beyond linearity, which can be interpreted as a positive value, making the total complexity higher than the simple addition.

Another manifestation of interlayer coupling is feedback loops: systems tend to form a closed loop between multiple layers, with information flowing back and forth between layers until some equilibrium is reached. For example, in automatic control, the sensor data (D) is processed to obtain state information (I), and the decision-making module (W) calculates the control command according to the target (P) and the knowledge model (K) and acts back to the environment, and then the environmental change affects the new data - forming a closed loop. If the system has to carry out a perception-decision-action cycle H times in a task, then the total complexity can be roughly regarded as the sum of the complexity of each layer at a time, i.e.,

.

.

The P-layer is not considered here, as the target is usually unchanged within the loop (if the target is also adjusted, it should be counted as the P-layer complexity). This equation shows that if the system needs to continuously perceive decisions (e.g., autonomous unmanned systems cycle multiple times per second), the complexity increases linearly with the number of cycles. However, with feedback conditioning strategies, it is often possible to reduce the number of effective cycles. For example, the introduction of feedforward prediction can skip part of the loop, or the perceived frequency can be reduced by filtering, which will reduce the equivalence. In extreme cases, if the system reaches a steady state and no further adjustment is required, it can be considered to be reduced from a certain value to 0.

To describe the evolution of complexity more precisely, consider a discrete-time evolution model: let the complexity cost of representing layer i in the tth decision cycle have:

It may be a function driven by an external input, such as a change in the rate of arrival of data;

It may be a function driven by an external input, such as a change in the rate of arrival of data;

The complexity of the knowledge layer changes with its own accumulation and the introduction of new information.

The complexity of the knowledge layer changes with its own accumulation and the introduction of new information.

The complexity of the intelligence layer is affected by the effectiveness of the current knowledge and the progress of goal completion.

The complexity of the intelligence layer is affected by the effectiveness of the current knowledge and the progress of goal completion.

, the complexity of the intent layer is updated based on whether the new target switch is triggered and whether multi-agent coordination is carried out.

, the complexity of the intent layer is updated based on whether the new target switch is triggered and whether multi-agent coordination is carried out.

Such a model describes the cyclical dependence of complexity: the complexity of each layer affects and co-evolves over time. For example, if there is a drastic change in the external environment at a certain moment, resulting in a large increase in data input (a surge), it will also be pushed up in the short term because more information needs to be processed and more decisions need to be made; However, in the long run, if the system extracts a new model from a large amount of data through knowledge learning (rising), or updating the strategy (reducing the future), the complexity of the subsequent cycle may decrease. It can be said that complexity can be eliminated between different layers: the increase in the complexity of the data and information layer may be exchanged for a decrease in the complexity of the knowledge layer (because the system is smarter and does not need blind search); The reduced complexity of the intelligent layer may mean that more complexity is pushed forward to the knowledge layer for offline processing (such as pre-trained models). This transfer and balance of complexity reflects the core idea of intelligent system optimization: transform real-time complexity into preprocessing complexity, and transform low-level complexity into high-level complexity to achieve optimal overall efficiency.

An edge case worth discussing is: does more layers mean more complexity? On the surface, the introduction of more layers will inevitably increase a certain amount of overhead (at least the basic processing of each layer requires resources); On the other hand, more layers provide greater structuring capabilities that reduce the complexity of each layer itself. As Simon points out in The Architecture of Complexity, the hierarchical structure of complex systems is a means of dealing with complexity. Therefore, the DIKWP five-layer architecture does not necessarily increase the total complexity compared with tiling all problems, but may reduce the overall complexity through division of labor and abstraction. The way to measure this is to refer to the concept of effective complexity: it distinguishes between regular parts of a system (compressible patterns) and unordered parts (random complexity). The hierarchical structure of DIKWP helps to separate the ordered part of the problem (the knowledge and wisdom layer deals with structured problems), and the disordered part is limited to the low layer as much as possible (the data noise is handled by the information layer), so as to reduce the effective complexity of the whole world. In other words, despite the complexity of each layer, with a proper architecture, the overall complexity of the system increases more slowly than without architecture, and even reaches some upper threshold.

Mathematically, you can try to define an overall complexity metric. One possibility is to borrow Tononi's concept of Integrated Information and use the Φ value to quantify the complexity and integration of the system as a whole. It depicts the part of the system as a whole that produces more information than the sum of its parts. In the DIKWP framework, if we consider each layer as an information processing module, then the stronger the interlayer coupling and the more integrated the system, the higher its Φ may be. The level of Φ can be understood as the overall complexity of the system (which cannot be explained by the individual parts). This measure is particularly relevant for artificial consciousness systems, as Φ is considered by some theories to be associated with the degree of consciousness. In terms of complexity, the complexity of a high-Φ system is not the sum of the discrete parts, but the parts that have a large number of interactions. This means that the analysis of such systems requires consideration of the contribution of interlayer coupling, i.e., the ** term in the above formula.

Summarizing the above discussion, it is quite complex to accurately describe the overall complexity. However, we can summarize a few rules:

Linear approximation stage: When the system is in the early stage of the task or does not change much, each layer performs its own role, and the complexity approximation can be decomposed into the sum of the layers. In this case, the interlayer coupling plays a small role and can be approximated as 0,.

Coupling enhancement stage: With the development of the task, the interlayer information flow is frequent, and the coupling term rises. For example, when encountering a difficult problem, the wisdom layer frequently calls the knowledge layer (), or the data fluctuation triggers multiple rounds of feedback ( ,

,  etc. positive values). At this time, the growth is faster than linear, and even there is a non-linear jump.

etc. positive values). At this time, the growth is faster than linear, and even there is a non-linear jump.

Stable synergy stage: The system strengthens inter-layer synergy through learning and adaptation, and higher-level patterns emerge, and some couplings become less complex (negative). For example, the improvement of knowledge simplifies the intelligence layer, and the stability of the wisdom strategy reduces the demand for data. Growth slowed or even declined.

New Target Shock Phase: If a new intent or environmental mutation is introduced, a new coupling enhancement process begins, repeating the cycle.

This evolution can be fitted to some extent with piecewise functions or piecewise linear models, i.e., different growth rates for task size (or time) at different stages. For complex systems, we are more concerned with long-term stability: whether there is some mechanism that prevents indefinite deterioration. The biological brain, for example, is obviously an extremely complex system, but the human brain is astonishingly efficient at routine cognitive tasks, far from the level of a combinatorial explosion. This is thought to be due to the brain's hierarchical structure, highly parallel computation, and continuous adaptive optimization (which strengthens valid connections and weakens unwanted ones), which reduces overall complexity.

In line with this line of thinking, in order for AI systems to achieve large-scale cognition and controllable complexity, they must also use the structured approach of DIKWP to divide and solve problems in layers, and reduce unnecessary searches and computations through feedback learning. In the language of complex systems theory, it is to reduce entropy to dimensionality: to reduce the degree of freedom of the system so that it actually behaves on a low-dimensional manifold in a high-dimensional space. The interaction of the various layers of DIKWP is precisely to continuously constrain the effective state of the system, from data to intent, so that the complexity does not expand endlessly. This creates a closed loop of complexity evolution: the system senses complexity, processes complexity, learns to reduce complexity, and repeats itself to maintain efficient operations in a dynamic environment.

Case Study: Application of DIKWP Complexity in a Typical System

In the following, we analyze the complexity performance and optimization strategies of the DIKWP model in the actual cognitive intelligence system through several typical case scenarios. These examples include: AI education systems (intelligent teaching systems), autonomous unmanned systems (such as unmanned vehicles/drones), and multi-modal large model platforms (large AI model platforms with multi-modal interaction). By dissecting the layers of DIKWP in each scenario, we will see the complexity characteristics of different applications and discuss how to take measures to optimize the system complexity at each layer.

Case 1: Analysis of the complexity of the AI education system

Scenario description: An AI education system refers to an intelligent teaching and tutoring system, such as a personalized intelligent tutor for students. The system captures student learning data, provides instructional content and exercises, and dynamically adjusts instructional strategies for each student. We take an intelligent teaching system for mathematics tutoring as an example to investigate its complexity source and DIKWP hierarchical performance.

Layer D (data): The data of the AI education system includes students' practice answer records, classroom interaction logs, physiological sensing data (such as attention monitoring), etc. The complexity of the data layer is reflected in the large amount of student answering information that may need to be processed, especially on an online teaching platform, where thousands of students interact with the system at the same time. For each student, data input includes the time each question was answered, whether it was correct or not, the process of solving the problem (e.g., steps or ideas, which may be in text), and behavioral data such as mouse clicks and time spent on the page. Combined, these data points are quite large. Assuming that each student solves 100 questions a day, and each question records 10 data points (time, true or false, steps, etc.), and 1,000 students generate data points every day, the complexity of the data layer is equivalent to processing millions of data levels per day. If the system is also connected to the camera to capture the students' expression concentration, the video data volume is even larger. However, in general, such systems will preprocess and extract simplified information from the video to avoid the complexity of the data layer. Optimizing the data layer includes aggregating log data in real time (reducing storage frequency), reducing frame rate or resolution for video capture, and reducing the amount of invalid data through event-triggered mechanisms rather than continuous sampling. These can effectively reduce the data layer.

Layer I (Information): The information layer needs to extract meaningful information from the raw student data. For example, the mastery of each knowledge point is calculated according to the answer record, the thinking characteristics of students are extracted from the text of the problem-solving steps, and their learning habits are inferred from the operation behavior. These belong to the process of feature extraction and information fusion. For each student, the system may maintain several features, such as "mastery percentage/memory intensity", etc., which involve aggregating a large amount of problem data and calculating statistics, which are usually linear or linear logarithmic complexity, such as summarizing the accuracy of each knowledge point ( ) or doing a sliding window to count the forgetting curve (possibly). In addition, multimodal data fusion also increases C_I: for example, combining answer records with expression attention data can determine whether a certain type of question is wrong due to carelessness (decreased attention) or lack of knowledge. Multi-source information fusion may require matching timestamps or related events, which introduces a certain degree of combinatorial complexity, but because each fusion is mainly carried out in the same student dimension and the scale is not large (hundreds of data points matching), it can be considered that the C_I still grows nearly linearly with the amount of student data. The key to optimizing layer I is to pick out valid features and avoid "unnecessary information extraction". Common knowledge tracking models in the education system (e.g., Bayesian Knowledge Tracing, Deep Knowledge Tracing) replace a large number of manual feature extractions, which update a few parameters in real time (e.g., mastering probability) through a relatively simple model, shifting the complexity from processing all historical data to updating one model parameter (similar to O(1) operating on each question). Therefore, the introduction of the student knowledge state model greatly reduces the calculation of the information layer: it is no longer necessary to recount the full data every time, but to update it incrementally. In summary, the complexity of the information layer of the AI mentor system is quite low when there is model assistance, and more calculations are transferred to the offline model training stage (which belongs to the knowledge layer or intelligence layer preprocessing).

K layer (knowledge): The knowledge layer of the teaching system consists of two parts: one is the subject knowledge base, which contains the structure of the teaching content (knowledge point relationship, exercise database, etc.); The second is the student knowledge state model or database. For subject knowledge bases, the system needs to retrieve relevant content to recommend the next question or knowledge point to students. For example, when a student makes a mistake about a quadratic equation, the system needs to find out the prerequisite knowledge (such as a primary equation) of the corresponding knowledge point from the knowledge graph to provide review materials. This retrieval complexity depends on the size of the knowledge graph K and the depth of the query. In general, the scale of the subject knowledge graph is not huge (thousands of knowledge points and relationships), and the retrieval usually uses node indexes to quickly locate relevant knowledge points (C_K close to O(\log K) or constants). Therefore, the knowledge base part is less complex. The other part is the student knowledge status, which records each student's mastery of each knowledge point, which is equivalent to a matrix (student × knowledge points) or database query. If you serve M students at the same time, you need to find the student's data in M records for each knowledge point status update retrieval. Per-student storage with a hash table is available at O(1). If the storage is categorized by knowledge points (student mastery in a list of knowledge points), then updating the status of a student's knowledge points requires finding the students in the list (complexity O(\log M) or O(1)). So either way, the complexity of a single update or query is not high. However, the student status database is updated frequently (each question is triggered), and the total complexity accumulation cannot be ignored. If M=1000 students update state 10^5 times per day, the state library needs to undertake 10^5 small-scale write operations. Fortunately, the database management system can handle this concurrency efficiently, making it scale well. In general, the main challenge of the K layer of the AI teaching system is not the retrieval complexity, but the knowledge evolution: for example, dynamically updating the parameters of the student model (learning rate, forgetting curve), or modifying the knowledge structure according to the student data (if two knowledge points are found to be strongly related, they may automatically add new connections in the knowledge graph). The latter involves the learning of knowledge structures, which belongs to the intersection of the wisdom layer/knowledge layer, and its complexity is difficult to quantify, but this update is usually carried out offline and does not affect the online complexity. With pre-orchestrated courses and a well-built knowledge graph, the amount of computation at the K-layer at runtime is minimized.

Layer W (Wisdom): The wisdom layer is embodied in the teaching system for teaching strategy planning and personalized decision-making. For example, the system needs to decide what to present next, whether to explain, give examples, or let students practice. If you practice, which question to choose; When students are not performing well for a long time, whether to adjust the overall learning strategy, etc. These decisions are multi-objective in nature (both to be efficient and to keep students interested) and involve a certain depth of planning (planning the next few learning steps to achieve an overall goal, such as passing an exam). The decision-making space is very large: assuming that the system has 10 different teaching methods, each corresponding to a variety of content choices, then each step of the decision can be seen as a sequence of picking from many options. The wisdom layer is often solved by rules or algorithms: for example, simple If-else rules (if the mastery is low, the basic questions will be explained first), and the complexity of this hard-coded strategy can be ignored (constant time decision); Or use the teaching strategy model trained by reinforcement learning, which directly outputs actions according to the current state during interaction, and each step of the decision is also calculated as O(1). However, in order to obtain these fast decision models, complex planning algorithms or training algorithms may be used behind them. Taking reinforcement learning teaching as an example, offline training needs to simulate thousands of students interacting with the strategy to iteratively update the strategy, and search the huge policy space to find the optimum, which belongs to the preprocessing complexity of the intelligence layer. When running online, this complexity is implicit in the model and is greatly reduced when it is actually executed. Therefore, the complexity of the intelligence layer of the teaching system shows two stages: the offline policy design stage may be an NP difficult problem (for example, the optimization of the teaching process can be regarded as a class of combinatorial optimization), but the complexity of the online execution stage is constrained at a very low level through models or rules. If a system doesn't have a pre-trained strategy and instead executes planning in real time, the complexity increases. For example, some adaptive learning systems run algorithms in real time in the background (such as calculating the learning path of the day based on student performance), and if the algorithm needs to search for many combinations (for example, selecting 10 questions and selecting the best combination from 1000 questions in the question bank, which is equivalent to a large number of combinations), even if a heuristic greedy algorithm is used, it may also have to evaluate the effect of many alternative questions, and the complexity should not be underestimated. Optimization methods include: limiting the set of optional content (e.g., selecting topics from adjacent content of knowledge points instead of the whole database), applying heuristic rules to filter options first, and making phased decisions (first determining knowledge points and then specific topics). These measures can reduce the decision-making space S or effectively reduce the number of alternative strategies G. Therefore, in practice, a mature AI mentor system usually simplifies intelligence-layer decision-making to a limited selection of a few strategy templates, so as to avoid completely groundbreaking planning teaching. In summary, at the intelligence layer, complexity depends critically on the degree of pruning of the decision space: if the pruning is sufficient, it C_W close to constant or linear, and if it is not sufficient, it may explode. However, with years of teaching experience and AI algorithms, this problem can be well avoided.

P-layer (intent): In the AI education scenario, the top-level intent is generally clear and stable—to help students master knowledge and pass exams. This is a human-given goal at the beginning of the design of the system, and it does not change frequently. Comparatively speaking, the intent layer complexity is mainly reflected in multi-student management and teacher/parent requirements. For example, an AI education system serves many students at the same time, and each student's learning goals and progress are different, so the system needs to make trade-offs in resource allocation (such as server computing power tilt and content recommendation priority). If the system needs to constantly adjust the schedule based on each student's priorities (e.g., students approaching exams prioritize more intensive services), then it can be seen as a task scheduling problem on a global scale. But usually this kind of scheduling is more at the engineering implementation level and does not affect the teaching strategy itself. Therefore, it can be considered that the overall intent of the system is unified (to improve the learning effect), but the external constraints (time, resources) may bring some scheduling intentions. Another aspect is multi-agent collaboration: AI tutors may work in tandem with human teachers, which requires strategic consideration of the teacher's plan (e.g., what knowledge points the teacher asks to cover today, then the AI mentor's intentions need to be temporarily subordinated to the teacher's arrangement). This kind of collaboration can be abstracted as the intent fusion problem of different subjects, but in practice, it is usually determined by preset rules and is not very complex. In summary, the intent layer of the education system is relatively simple, with a low T (number of target switches) that only changes when external requirements change or curriculum objectives are adjusted; L (Adjustment Feedback Loop) may manifest as adjusting a class schedule or study plan once and then executing it. As a result C_P does not contribute much to the overall complexity. However, in the future, if we imagine an AI education system that can independently plan long-term learning paths and dynamically adjust the syllabus, then the intent layer will be more active. For example, the system may find that a student is interested in programming and temporarily add a long-term goal to cultivate that direction, which is equivalent to introducing a new goal at the intention level, which needs to be coordinated with the original subject learning goal for long-term planning. In this case, the C_P will increase, but this kind of autogenization is still at the forefront of exploration.